Wilhelm and I stood in the corridor, the scenery afforded to us by the long windows was but a small compensation for the lack of insulation between the elements outside. We shivered in our failure of hooded jackets and REI thermal shirts. I planned to personally slap the REI product developer in the face upon my return to the US, wondering if the company had bothered to test their cold weather products in actual cold climates.

Anka was busy typing her new screenplay while her husband and I stood there. Ekaterinburg six hours before had marked the entry into European Russia and away from Asian Russia. Despite the subzero temperatures I was ecstatic to be one train track closer to the West. Lanky pine trees replaced the naked birches, and the Ural Mountains, covered in forests and soggy black log cabins, stretched into the horizon. Visions flashed in my dreams of traipsing the mountains, which time had worn down to gentle hills, all the way south through the Caucuses down to the Caspian Sea. I had to remind myself that they awaited me in a few weeks’ time, just as this journey bided its time for me for eight years years, readying itself to welcome me as a guest in a time when I didn’t even know the invitation existed.

Visions of the Transiberian Rail journey entered my consciousness a lifetime before, when I shared a beer with a Stanford University drop-out at a Krakow hostel and he mentioned he was headed to Beijing to teach English, and would take the train on the way. At the time, I wanted to drop everything and tag along. But I had school to finish in Spain, and then life was to unfold–military service, disability, marriage, divorce, things like that. But finally, years later, the chance to take the journey came again. It’s how I found myself nearly five days into the six-day trek from Beijing to Moscow.

Wilhelm snorted in laughter, bringing me back to the present. “Look at this place,” he said, pointing to the razed artillery yards now coming into focus. Warehouses punctuated the endless forests, their windows blown out, leaving behind gaping holes and crumbling bricks. The tall watch towers, one right in front of us and the other in the distance, were both toppled over.

Cabins in the distance clung to rotten wood and corrugated steel, but were inconsequential compared to what was driving near the train. A bedazzled Hummer, equipped with multiple sets of blinding florescent headlights, platinum rims on the tires, and air-brushed designs on its hood, crawled at parade-route speed through the abandoned environs, like a UN aid truck with an identity crisis.

“Of course,” said Wilhelm, shaking his head. “Of course that would be here. This place looks like a war zone already. If not here, then where?”

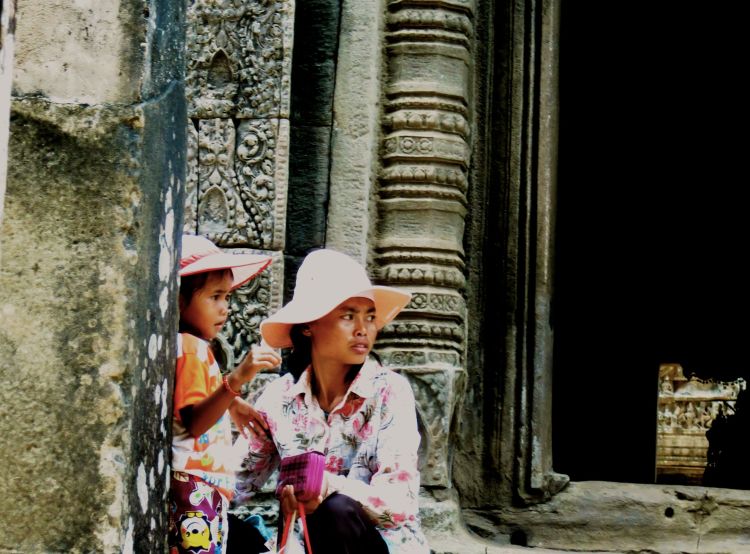

I smiled, although at that point Lady Gaga could have emerged from the crumbling warehouse or one of the acrobats from Beijing could have triple-flipped across the charred landscape and it wouldn’t have surprised me. Seven weeks into this journey–the child prostitutes in Thailand, the shattered skulls and blood stains in Cambodia’s Tuol Sleng prison, the dysentery and soldier ghosts in Vietnam, the police state in their designer clothes in China, and the drug smugglers at the border in Mongolia—nothing surprised me anymore it seemed.

The rain intensified, splattering the smeared pane. I bid my neighbors goodnight and returned to my cabin. Another frigid night awaited but I needed whatever traces of slumber the cold would be willing to provide. Moscow would greet me in less than 24 hours and I had to rest, to focus. The past 5 days ensconced on the train, sheltered from the countryside but still so exposed, may have been an ill preparation for the awaiting city.

This part of the journey, the one I thought I would dislike the most due to its crowd of people, its lack of privacy, and the wrought boredom, had been nothing like that. It had instead been my favorite part. The train’s sparse population, and the quiet and isolation of traveling with so few people at the beginning had compounded a broken heart. That part of the story, if it’s even worth telling, is for a different time. But as the days passed and the Siberian sun stretched and inevitable introspection forced itself upon me, I knew I would be okay even if I was alone. I just wish I would have known it weeks before. Or years before.

But it was unfair to judge the past and those things I did not know then. Perhaps all I had to begin with–myself–was all I ever needed.

At that point, the brooding and epiphanies no longer mattered. The train’s hypnotic sway rocked me like a lullaby as I crawled into bed. Four wool blankets piled on top of my body were my shield from the intrusive ice working its way through the berth windows. I closed my eyes as resignation, sorrow, contentment, and acceptance took their final waltz through me, and I remember thinking how well I would sleep that night.